turning the leaf: what even is time, let alone a calendar or an almanac?

One of the rites that I—and many of us—once did to mark the passage of time was to buy a new calendar for the new year. Remember all the choices of styles? Did you want to have a day view? A weekly view? Did you like yours lined or with an address book at the back? Was yours a planner or just a little reference book to jot dates in on the go?

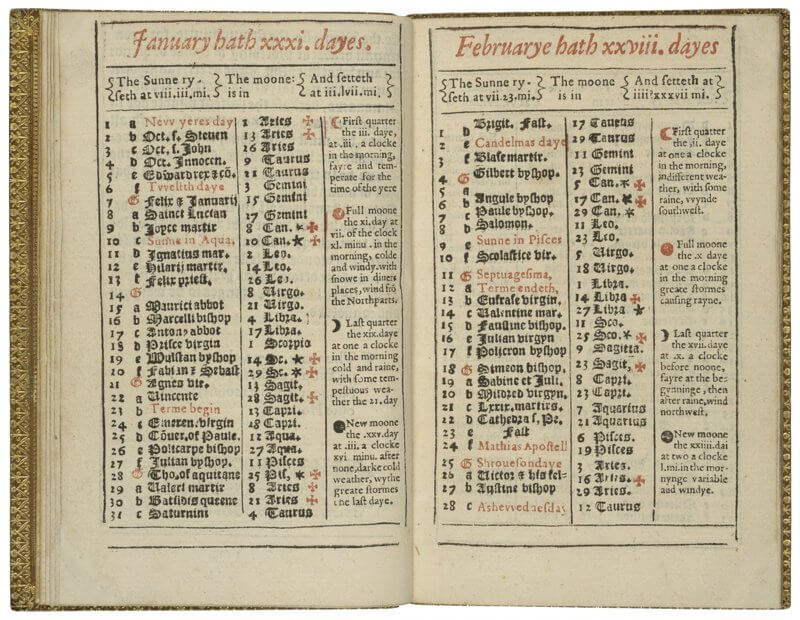

If I lived in the 16th or 17th centuries, I might have a similar range of options for my calendrical needs. Of course, those needs were less about what day of the week it is and generally more about saints’ days and the location of constellations and the moon and perhaps auspicious days for activities. In other words, they functioned more as ephemirides (tables of the locations of astonomical bodies at set times) or almanacs.

This 1631 almanac by Jonathan Dove leaves nearly an entirely empty page for users to add their own notes (although this copy seems entirely unused; you can see a similar but annotated one at the Wellcome: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/v2jpg3n9):

On the other hand, you might prefer one that incorporates the compiler’s observations about history, as in this Gadbury 1688 almanac:

Or maybe you’d like a compact one, where each month is only one page, as in this 1571 Securis?

Users could also purchase almanacs with blank pages bound in (“blanks”) or without such pages (“sorts”); they could buy all the almanacs issued for a single year bound together in a volume, if they wanted the full range of supplemental information that different compilers included; or a wall almanac consisting of a single-sided sheet of paper.

One of the things that these images of early modern almanacs don’t convey is how unusual it is that they survived in the first place. Because the printing of almanacs in London was controlled after 1603 by the Stationers’ Company, there are detailed records of the numbers of English almanacs printed annually. And every year, almanacs were printed in numbers that are frankly ridiculous compared to other print runs. Between 1664 and 1687, the number of Andrews almanacs distributed annually ranged between 10,000 and 30,000 copies. In 1687 alone there were over 460,000 copies of 30 different almanacs printed. Almanacs were certainly the most printed work during 17th-century England, helped in part because of their popularity, but primarily because you had to buy a new one every year.

It’s a truism in book history that the more popular a work was, the fewer copies survive. And indeed, libraries and book collections today aren’t overwhelmed with shelves sagging full of almanacs. What did you do with your old paper calendars? Dumped them in the trash, maybe recycled them, or perhaps shoved them forgotten in the back of a drawer where they were later used for scrap paper and nests for mice?

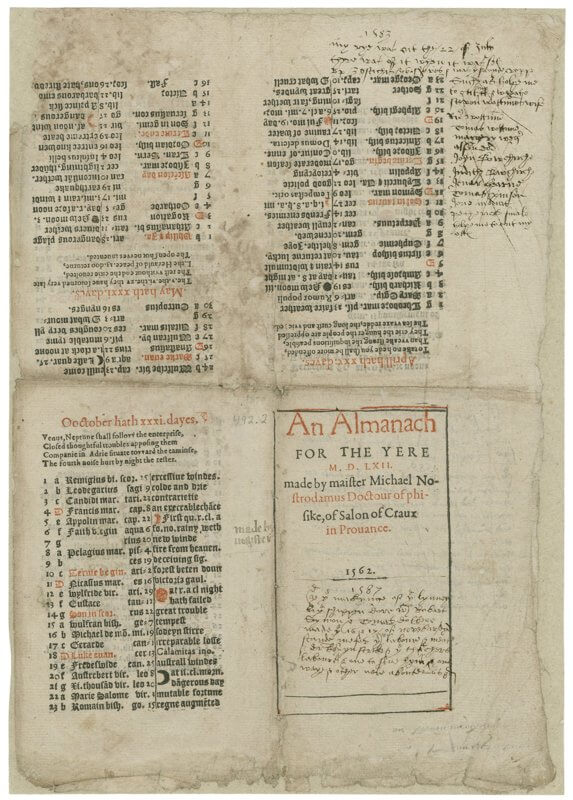

I like this 1562 Nostradamus almanac for a number of reasons, including that its user added notes for a number of later years (here you can see 1583 and 1587):

But also look at the state it’s in! You’re looking at half of a sheet—it looks like a quarto in this view, but it’s the right half of the outside forme of an octavo. (Both sides of both halves of the sheet are at https://www.earlyprintedbooks.com/shelfmark/STC-492-2/.) And that torn sheet isn’t even the complete almanac—it ends in the middle of October and the following sheet(s) are now lost. The ESTC records only a single copy of this alamanac, the one that is now held at the Folger (estc.bl.uk/S125187; but note that this doesn’t mean there aren’t other copies somewhere, only that the major libraries whose holdings are surveyed probably don’t have one).

Time is fleeting. But time is also not linear. Adam Smyth’s work on almanacs as a form of life writing suggests how rich a window they are into the ways we experience ourselves moving through time. Almanacs often contained printed information about different modes of time—how long it’s been since the world began, predictions for next year’s weather. Annotations jotted in an almanac were often transferred into receipt books or other volumes, turning the almanac away from being a record of time and into being a temporary container through which your life was poured.

The passage of time has been on my mind not only because it’s the start of a new calendar year, but because access to my local rare books library is in hiatus. All the images in this post have been taken from the Folger Shakespeare Library, a library where I learned to be a bibliographer and book historian and that has been my home base as a researcher for over two decades. The Folger will reopen in a couple of years, in a different form but with the same collections waiting to be used again. We will be different, too, in a couple of years. Our internal calendars and our external lives will have been spiraling out in ways we cannot predict. And yet we will still be ourselves, whether we’ve noted our journeys in now discarded platforms or in carefully collected and preserved observations. Time is elastic, we will walk through the Folger’s doors again, and if we remain good stewards, there will always be books and scraps waiting for us to use them.

about this page

“Featured Content” highlights images and resources on EarlyPrintedBooks.com and changes approximately every other month. (You can see when the content was updated by looking at the footer at the bottom of the page, which uses the YYYYMMDD format for its version number.) The material appears first on the newsletter Early Printed Fun and old content is listed below and archived over there. The newsletter includes issues in addition to what appears here; you can sign up at sarahwerner.substack.com.

archived content

“digitized images: why are they so weird?” October 24, 2019